ESSAY | Take Us With You

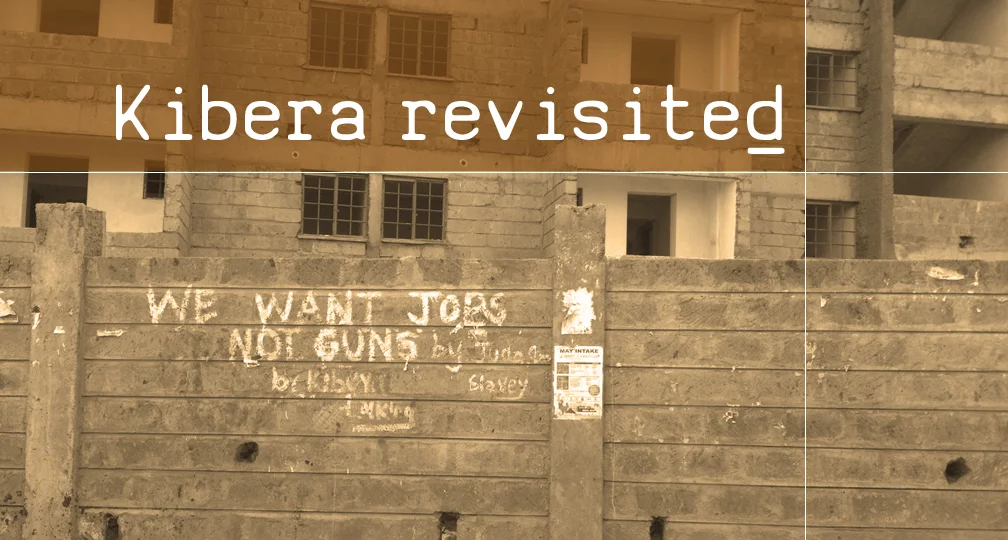

Things have changed in Kibera since I was last here.

There is a high-rise development in progress, a building stacked with cinder blocks towering over the rusty streets of Kibera. The gray towers might look dismal to the eyes of visiting outsiders, but to the eyes of the settlement dwellers, the cement towers look like marble palaces.

And, they are a luxury. Few Kiberans will be able to afford them despite the fact that they were developed with Kiberans in mind.

And, there is more crime in Kibera now. Or, so they say. And, because of the crime, I am only allowed into the settlement with two armed guards carrying, quite proudly, AK 47s.

They wait for me while I visit with the children at St Lazarus, the school where I am working.

The guards are careless with the well-polished guns - they’re careful to make sure the barrels’ metal plating gleams - but careless with them around the children.

When one guard, Ruben, sits beside me to ask me for help to find a way to attend college, I am holding a toddler. The child and I are having a moment as I sit on the clay ledge outside the classrooms, she looking into my face and nuzzling her head onto my shoulder.

And then Ruben sits down beside me. Momentarily, I’m irritated at the intrusion, but then, as the guard’s heart spills out into his words and the hardness in his eyes melts away, I see he is desperate to change his circumstances.

Still, I can’t take my eyes off of the barrel of the AK 47, pointed at the toddler who is learning to lean in and trust me. As Ruben grows more passionate about his needs and demonstrative with his hands, I ask him to point the gun the other way.

He looks perplexed. I point to the child. And, then he understands and points the gun towards the hard packed dirt below our feet.

When I visit Kibera the next time, I have to wait for the guards to assemble.

It’s a process, getting the guns and the guards and their uniforms together, and this particular day the ceremony takes hours as I wait at the guard station just inside Kibera. I don't mind, the streets of Kibera distract me as Kiberans stroll by me in colorful pageantry.

Slowly, I see a crowd of Kiberan women forming inside the gate of the guard shack.

Observing them, I think the glaring sun beating down on their scarve-wrapped foreheads is responsible for the angry scowls on their faces, but then I realize, there is more than sun in their eyes, there is scorn.

At that moment, I hear wailing. The sound of shame and despair is thick in the shrill screams of children.

I move through the gathering crowd of women and slip inside the shaky metal guard shack.

Dirt-streaked, barefoot and wearing torn t-shirts that look like they had once belonged to fashionable Americans, two young girls huddle together on the floor under the guards' guns and glares.

Jolted by my appearance on the scene, caught waving guns at wailing children, the guards expedite their dressing ceremony and, suddenly, the guards are ready to go with me to the school.

For three hours I work at the school while the guards wait for me. Then, we make our way past the produce stands, cell phone charging stations, and beauty shops that line streets of Kibera, back to the guard shack at the entrance to Kibera.

And there, the scowling women with the folded arms still stand.

And inside, in the darkest corner of the dark shack, the girls still sit, heads bowed.

I ask the guards why these girls spent their day siting on the floor of the guard shack.

"These young girls were so possessed with their budding womanhood," the guard says, "that they wanted to sleep with men and ran away from school."

“For money?” I ask, “Do they need money? Is that why?”

"No, they just can not control themselves and so their mothers are here to have me deal with them," he says in stilted English. "We found them hiding in the bush."

The proper English dictation and perfunctory grammar of the guard don't match the barbaric meaning of his words. It's hard to process the juxtaposition of the two - his gentlemanly accent and the gun pointing toward the sniffling girls sitting in the shadows.

The trembling girls in the childish t-shirts hardly seem like the seductresses the guard described.

I ask about the men, the men who had taken the girls into the bush.

“Who is going after them? Where are they?"

There is no answer. There is no mention of men so possessed with their masculinity and sexual prowess that they would take two prepubescent girls away from school, have their way with them, and leave them in the bush.

As the guards tower over the girls and their mothers and relatives look eager to cast the first stone, I cannot bear it anymore.

I slide down the corrugated wall and sit beside them, with them, in the dust and darkness, on the floor.

I reach out and stroke the smaller girl’s arm, and whisper my name and ask for hers.

“Faith”, she finally whispers.

“Please let me try to help you,” I say.

The girls look pleadingly into my eyes. And then bow their heads again.

“I don’t think you wanted to run away with the men,. Can you talk to me about it? I want to help you, how can I help you?”

The guards try to ignore me.

The women scowl and then continue to ignore all of us.

Their disgust and dismissal of our bonding moment inadvertently gives the girls and me a secret shrine of shame, a holy chapel of dirt, dust and darkness that houses our mutual prayers of "Why?" and "What now?"

And with the shaken Faith and her friend, I huddle in that dark shrine and shudder.

Until finally, the younger one speaks to me. Glancing toward the guard to avoid attracting his attention, she whispers, "Forgive us."

I am sure I look confused.

But, she persists, with tears spilling out onto her dusty cheeks, and says again, “Forgive us.”

These aren’t the words I expect. With the plea for forgiveness, Faith begins to cry too.

“There is nothing to forgive,” I say. “I can’t forgive you, you have done nothing wrong.”

But, still, in that dusty, dirty shack of shame, the girls had been told they needed forgiveness and they were determined to find it.

I hug them into my arms and say, “There is nothing to forgive, but if you need to hear that you are forgiven, know that you are forgiven. And, you are loved.”

With those words, the sniffling tears turn to quiet, convulsing sobs and in a matter of seconds their tears seep through my thin shirt and onto my collarbone.

The girls and I sit there in that darkness and cry together.

I cry for the shame that had been heaped on these girls and countless others like them.

I cry for their angry mothers who could not feel a maternal tug to nurture their broken daughters --because those mothers probably had their their own shrines of shame-filled shacks that left them with the permanent soul scars that now etch their faces.

And, I cry because there is nothing, in that moment, I can think to do for any of them, for any of us

Then, the girls speak the only other words they would speak to me that day,

“Take us with you.”

And my sadness turns to desperation.

Seeing how torn I am, they plead again, “Take us with you.”

I try to explain all of the reasons that I can't take them with me, but the reasons seem as hollow to my ear as they seem indiscernible to the Swahili speaking girls, and I curse myself that I have no power to take them with me.

Their mothers and the guards have plans to take the girls to the hospital to be checked for HIV. I know that these girls face an even more shaming afternoon.

I know that going home to a dark shack with the scowling mothers will heap more trauma onto their already traumatized bodies and souls. So, I try to fit as much love and forgiveness and kindness as I can into that holy moment on the floor of the guard shack, but I know the shaming to come will quickly erase any tenderness I give them

I finally have to leave, my driver is impatient and ready to leave the settlement, and the guards are growing wary about my time with the girls.

The girls and I hold each other in the dark corner for a few last desperate moments, the girls absolving my shame at my futility in such a moment, I repeating over and over, "There is nothing to forgive, you are loved."

The guard follows me to my taxi and, without shame, asks me if I might want to join him later for a date.

As I ride away in the bright Kenyan afternoon sunlight, the tears fill my eyes again as the words of the girls echo in my head.

"Forgive us. Take us with you."

In the little English that the girls knew and could speak in their terrified state, they summarized so much of the human condition.

In our moments of shame - whether the shame is deserved, or self, or other-imposed-don’t we all just want to be held, forgiven, and told we are loved?

And, for someone -anyone - to take our hand and take us with them?

Out of our darkness, and into the light.

Essay Data:

Written by: Millicent Smith